The drivers of FMCG in South Africa

As explained in the WOW report on fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) trends in South Africa, FMCG covers all the things we buy daily including groceries or packaged goods such as food, beverages, personal care items, and household goods. This sector has evolved significantly over the last century due to various factors, including industrialisation, technological advancements, globalisation, and shifts in consumer behaviour.

Economic growth and the South African FMCG sector

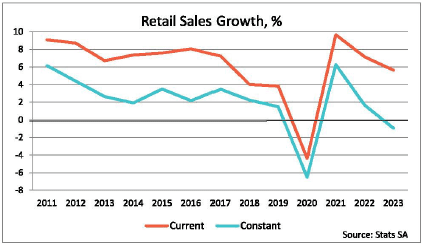

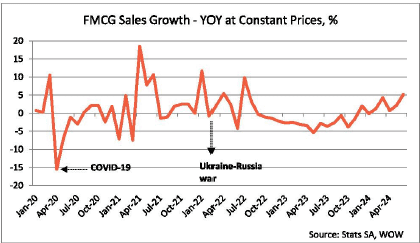

For manufacturers and retailers, the quest for growth is driven but also limited by population and income growth. With South Africa having one of the highest income inequality levels globally, FMCG companies experience challenges as they must cater for both low-income consumers and high-end markets. It is telling then that, sales of FMCG goods declined in 2023 as shown in the graphs below, according to the WOW report.

The graphs below illustrate how economic shocks like Covid-19 and the start of the war in Ukraine can affect industries. More concerning circumstances such as low economic growth, high inflation and high interest rates have a much more fundamental and long-term impact.

The most difficult of the primary culprits is of course low economic growth. In South Africa that growth has been so low, and in fact lower than the population growth, which inevitably contributed to a drop in income per person.

The government introduced initiatives such as Operation Vulindlela, a joint initiative with the National Treasury, focusing on structural reforms in sectors like energy, telecommunications, and water. While these measures have spurred some sectoral improvements, overall economic growth remains constrained. Investors remaining cautious and staying on the sidelines, has also been a limiting factor.

The extended period of high unemployment, negative real salary increases and high interest costs have increased the stress on FMCG retailers in the fight for market share and profitability growth. In their response to the trend of buying down, which was very noticeable in 2023, they have added lower cost private label products and are seeking further expansion in townships, which are underserviced in terms of larger retail space.

The pros and cons of technological advancement

On the one hand, technological advancements opened market opportunities for the FMCG sector in areas like online retailing, but on the other, it brought about heightened competition by enabling more players to reach consumers and innovate rapidly. With the rise of ecommerce, smaller and niche brands can now compete alongside established names, leveraging digital platforms to gain visibility without the traditional costs of brick-and-mortar retail.

Improved logistics and better information about the industry and consumer sentiment has seen a change in focus. There have been shifts in focus to online shopping and sustainability. Online shopping growth by far exceeds overall growth of the FMCG market and is expected to continue in the foreseeable future.

How big brands are tackling the township economy

A more interesting development in South Africa is the realisation of the size of the more informal trade in townships which runs into billions of rands. Advancements in logistics and technologies for stock management and distribution, as well as deeper market insights with the help of AI, has the big retailers and manufacturers taking township spaza shops seriously.

BevCo, a subsidiary of multinational Pepsi, is selling directly to spaza shops, bypassing wholesalers and saving on distribution costs. BevCo told Daily Investor that the single biggest challenge to entering the informal market is undoubtedly the vast number of stores.

“Nobody has exact data, but most research articles estimate there to be around 150,000 spaza stores in South Africa,” BevCo stated.

Sustainability in the FGMC sector

The sustainability issue revolves mainly around the reusability and recyclability of packaging. An innovative idea of selling decanted products to communities by NGOs such as Wakanda, will certainly be impeded by recent incidents of children being poisoned by contaminated food items purchased at local spaza shops.

However, packaging is almost a non-negotiable for premium brands which also use shrinkflation as a means to increase profitability. For example, some chocolate bar previously in paper packaging have become smaller and thinner (fragile), needing solid cardboard packaging over and above the silver covering to maintain freshness.

The African expansion of successful South African retailers has confirmed that many things have to be in place for a successful investment. To tap into the township economy and African countries, requires innovative ways of making products affordable while addressing logistical challenges. Logistics, import-export duties, currency and exchange controls can create an unwelcome and unprofitable environment.

In South Africa, the FMCG sector appears to be on a moderate growth path, aided recently by the new political dispensation and the prospects of lower interest rates.

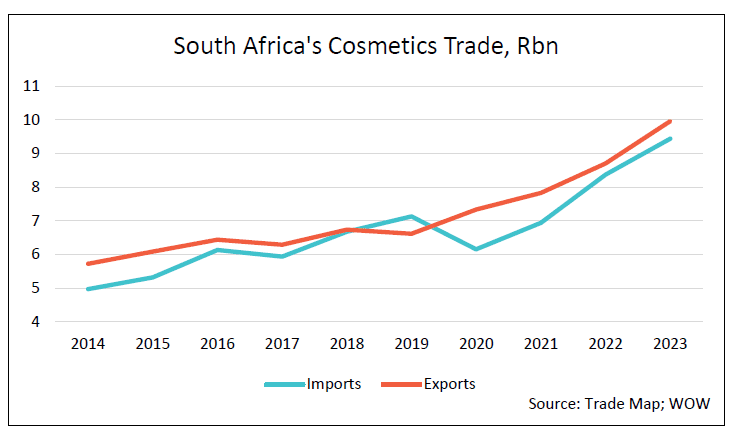

South Africa’s cosmetics industry has grown significantly over the past few decades and evolved from a market once dominated by international brands into a vibrant sector with dynamic local brands. The WOW report on South Africa’s cosmetics industry states that the cosmetics and personal care products industry is one of the fastest-growing consumer markets, with sales of cosmetics growing more than 15% annually.

According to Statista’s beauty, health and household care in South Africa report, growth has been driven by changing consumer preferences and its diverse consumers. An increase in male grooming and rapid urbanisation, from 63% in 2012 to 68% in 2022, has resulted in changing lifestyles and an increased focus on personal appearance.

Past Growth and Key Milestones

Historically, global beauty giants like Estée Lauder, Revlon, and L’Oréal were the mainstays in the local market, setting the standards for beauty and personal care products. The market was characterised by the prevalence of imported luxury cosmetics for lighter-skinned people, that largely excluded African skin tones and textures.

After the 1990s, the cosmetics industry began to shift with the newly empowered middle class having more disposable income, spurring demand for a wider variety of beauty products. This led to market expansion, driven by an increasingly diverse consumer base that was looking for products that catered to local needs.

Local entrepreneurs saw the gap in the market, and started researching local ingredients like rooibos, marula, aloe and baobab that gained recognition in the beauty world. The decision in 2016 by L’Oréal to open its first research and innovation centre in South Africa is an indication of the potential and possible competitiveness of this industry.

The Rise of Local Brands and Inclusivity

Local brands have developed to reflect the country’s cultural and demographic diversity. Brands like Sorbet, Africology and Portia M are examples of how local companies are responding to the specific needs of South African consumers, particularly those with darker skin tones and afro-textured hair.

As reported in the WOW report on the cosmetics industry, women-owned skincare brands have also been on the increase. Lelive, a skincare venture launched by the Swazi-born South African actress, model and TV personality Amanda du-Pont, Skoon, and Chick Cosmetics. These are just a few of local productions that are making inroads in the industry.

Impact of COVID-19 on the Cosmetics Industry

With the disruption of supply chains impacting the availability of cosmetics in the pandemic, several new trends emerged. Consumers began to focus more on self-care, driving demand for skincare products, hair treatments, and wellness-related beauty items. Consumers prioritised face masks and sanitisers over cosmetics. Social media was full of DIY skin and hair care products, driving awareness about how simple skin and hair care can be.

On the other hand, brands quickly pivoted to meet this demand, with some producing hand sanitisers and personal care items as part of their range.

The pandemic also accelerated the shift to ecommerce. South African cosmetics brands that did not have a strong online presence scrambled to build ecommerce platforms and leverage social media to reach their audiences. Influencers and beauty consultants were driving brand visibility, and digital marketing strategies became key for competitiveness.

Future Opportunities in the Cosmetics Industry

South Africa’s diverse population offers a unique market for brands to develop inclusive products that cater for various skin tones and hair types. As consumers become more educated about ingredients and sustainability, there is a growing demand for products that are free from harmful chemicals and that are ethically produced.

Wellness is another growth area, with beauty increasingly being seen as part of a holistic approach to health and wellbeing, both inside and out. This has led to the rise of beauty supplements and nutraceuticals, which offer skin, hair, and nail benefits from within.

South African cosmetics brands have the potential to expand beyond our borders, tapping into the growing global demand for African-inspired beauty products, particularly Europe, North America, and other African countries. From a market dominated by global brands to one that is increasingly local, inclusive, and sustainable, the industry reflects the dynamism of South African consumers.

While challenges such as skin-lightening controversies and environmental sustainability remain, the industry holds promising opportunities for brands that innovate and respond to the evolving beauty landscape.

South African parents pursuing quality education for their children in a technology-driven world are concerned about ensuring that their children get education that is aligned with market demands, and improves employability, as employers increasingly prioritise candidates with relevant tech skills and qualifications.

The quest for quality education in South Africa

With the high unemployment rate of graduates in South Africa, parents are faced with the conundrum of finding a “good school” within reach, physically and financially. When considering a university, reach becomes less important as students may apply to multiple universities, ranked by preference based on perceived reputation of the universities to ensure acceptance. The power of universities to attract students lies more on potential for their graduates to be attractive to the job market rather than on location and cost.

How perceived reputation impacts choice of university

Throughout this cycle, reputation and perceived quality of education are central in people’s choice of institutions to attend. Post-secondary education, the future value of the curriculum becomes a primary concern as the value of a qualification is associated with the institution awarding it.

Policymakers in education seem to have lost the way whereby they have established a multitude of institutions overseeing the sector with a plethora of NQF credits for certificates awarded but have not addressed the gap or shortage of sought after skills in business which remains despite the many institutions including the SETAs offering courses.

The WOW report on the education industry in South Africa delves into the status and achievements of the education industry. The report also outlines the role of different institutions of the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA), which oversees the National Qualifications Framework (NQF), and the quality councils which are responsible for the accreditation of qualifications and institutions – the Umalusi Council for Quality Assurance in General and Further Education and Training, the Quality Council for Trades and Occupations and the Council on Higher Education.

Emergence of edtech in South Africa

In this context, education technology (edtech) is emerging as a transformative force all over the world, and South Africa is grappling with integrating technology into teaching and learning. The education sector in South Africa is offering solutions to some of the challenges, particularly in promoting access through the installation of fibre that connects schools to the internet. This is aimed at bridging gaps between urban and rural schools.

While connectivity is key in driving the adoption of technology, the majority of rural schools and universities are still lagging behind in ensuring that each learner or student has a connected device to access education content.

The adoption of edtech (mostly by private sector companies) in South Africa is being driven by several key trends that are reshaping the education landscape.

Digital access and inclusion

Edtech solutions are helping to close the digital divide through mobile-friendly learning platforms, affordable tablets, and online resources, making education more accessible to students, regardless of their geographic location. Initiatives to provide devices and connectivity in underserved areas are, sadly, hampered in certain communities by criminal activities.

Teacher empowerment and training

There has been some progress in upskilling teachers to integrate technology in their teaching and learning methods, but access to high-quality professional development opportunities remains a hinderance. Virtual workshops, online courses, and collaborative platforms are slowly being utilised to train teachers to integrate digital tools into their classrooms.

The pandemic was a catalyst for the adoption of remote and blended learning models. South Africa, like many other countries, saw a rapid shift to online learning during lockdowns with technology companies leading the way and driving the change. Lecturers and teachers who were reluctant to venture into online education have now realised its value, and are slowly adapting to the hybrid method.

Challenges with qualification standards

The multiple authorities overseeing education, including the South African Qualifications Authority and various quality councils for basic and higher education, are now faced with the task of recognising different qualifications brought about by edtech platforms that make it easier for students to earn, track, and showcase their qualifications.

The main challenge associated with the multiple authorities is the lack of coordination, leading to confusion around qualifications and inconsistent benchmarks, making it difficult for students, employers, and institutions to navigate and evaluate the educational system effectively.

So far, the growth in enrolment at edtech private sector learning institutions is encouraging. Edtech focuses on specific practical skills that are in demand, enabling students to gain acceptance in the labour market, a process that has built edtech’s reputation.

The future of education in South Africa

While technology is playing an instrumental role in shaping the future of South Africa’s education sector, it is crucial to streamline qualifications, maintain high standards across institutions, keep abreast of technological developments and ensure equitable access to digital resources.

Since the new democratic dispensation, several national freeway systems were upgraded and tolls were introduced on key highways such as the N1, N3, N12 and N4. The South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) led these projects, ensuring that the country remains well-connected nationally.

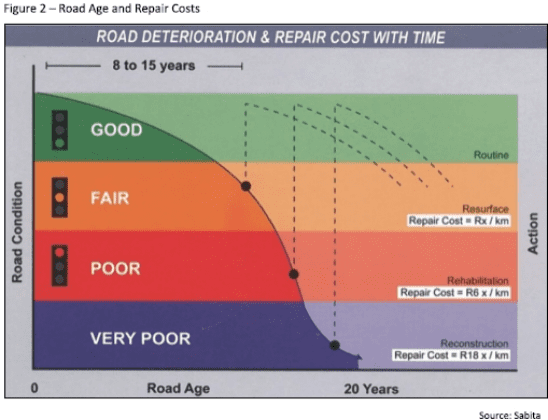

The WOW report on the operation of roads and tolls pointedly demonstrates how the cost of neglect and lack of maintenance has been pervasive in most of the country’s productive infrastructure assets.

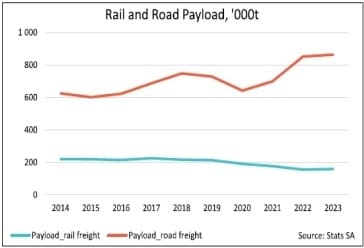

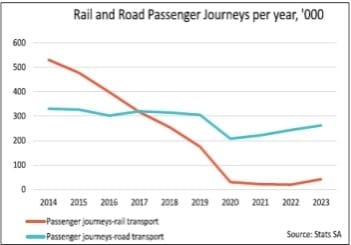

The report also illustrates how the significant backlogs in road maintenance of the provincial and rural road networks are contributing to the high cost of road building as government tries to catch up with the maintenance of the failing rail infrastructure.

The role of SANRAL in the development of key roads and corridors in South Africa

SANRAL successfully led the development and maintenance of national roads through a toll roads model, raising much-needed revenue through toll fees and private sector investment. The N4 concession contract in 1998 saw the private sector investing over R1.6bn in road infrastructure. Over and above that, government was included in a revenue share agreement with government. The success of this model led to the decision by government to replicate it through the e-toll system to cover the road upgrades required for the 2010 soccer World Cup.

Lack of maintenance and the cost thereof

The graph shown here illustrates how repair costs increase exponentially without proper maintenance. Between a 15 year old road and a 20 year old road, repair costs can increase by a factor of 18.

The lack of road maintenance has put the government in a predicament of having to budget far larger amounts than what could have been. This extra cost has been significantly augmented by the collapse and disuse of the railway infrastructure for passenger and freight transport, with heavy-duty rail freight transport moving to roads and causing an accelerated deterioration of many roads.

The graphs below illustrate the extent of the shift from road to rail over time.

Toll Roads

Two of the main considerations in toll road feasibility studies are the provision of alternative roads of an acceptable standard, and expectations that people would suppress (not take as many) trips.

The requirement to provide alternative roads was quietly removed from regulations to reduce the cost of building toll roads. Commuters were not able to suppress trips, such as going to work, and yet authorities chose to ignore the issue, going ahead to introduce e-tolls on urban roads.

The appeal of e-tolling technology and the prospect of high income to fund the World Cup blinded decision-makers to the downsides of not considering alternative roads for commuting. Prospective high toll fees caused SANRAL to concede to excessive costs to build and upgrade the road network in time for the World Cup.

Warnings of failed e-toll experiments in other countries such as Portugal were ignored. Lowering the tariffs and offering amnesty for non-payers were of no use as public outcry and obstruction to e-tolls persisted. The secrecy around the ownership and beneficiaries of the e-toll scheme added to the resistance by the public to the initiative.

Lessons learned

There are valuable lessons to be learnt. Timeous and effective maintenance of roads is critical to avoid huge repair costs. Government’s approach when embarking on the e-toll system highlights the importance of public consultation and transparency. Sustainable economic growth for the country will require stronger governance, better planning, transparent budgeting, cost control and proper oversight going forward.